Recuperar el pasado entre el miedo al futuro

La pandemia ha cambiado algunas de nuestras costumbres preconcebidas y, también, nuestra manera de convivir y de trabajar, pero no ha sido un impedimento mayúsculo para continuar recuperando la memoria histórica. Aunque durante la parte más dura del confinamiento sí se detuvo toda actividad no esencial, los trabajos en las distintas fosas localizadas en el estado han vuelto adaptándose a las nuevas medidas. Además de las complicaciones provocadas por el protocolo de seguridad y la dificultad de trabajar más de dos personas juntas al tratarse de un espacio reducido, el mayor daño que provoca esta crisis en las labores de exhumación es la falta de visitas de familiares. Aunque pueda parecer un hecho irrelevante, es fundamental para la comparación con el ADN de los restos enterrados para poder identificar a las víctimas. Por suerte, la relajación de medidas está permitiendo que vuelvan las personas que quieren que los suyos descansen, al fin, en paz.

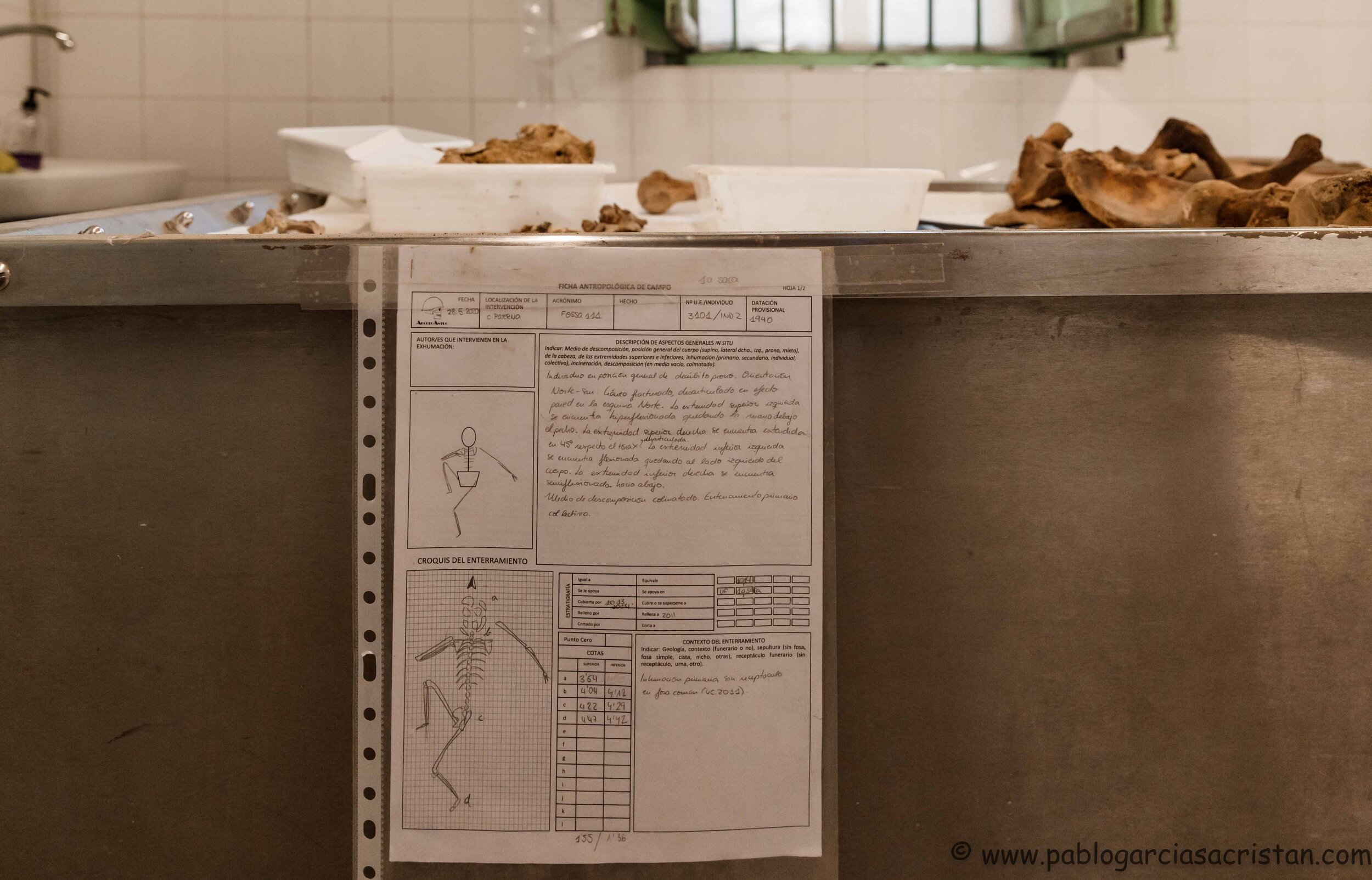

Es el caso del cementerio de Paterna, en Valencia, el cual es conocido como “la fosa común de España”, ya que entre sus paredes se encuentran más de sesenta fosas comunes y en torno a 2.300 personas fusiladas. Aunque el 15 de marzo se detuvo todo, desde principios de abril se pudo volver al trabajo. Actualmente, las labores se centran en la fosa 111, con más de 150 personas enterradas que fueron fusiladas (según los datos que se conservan del registro y los recuerdos de familiares) entre finales de marzo y el primero de mayo de 1940. En cada saca se terminaba con la vida de unas 50 personas, que se trasladaban sin vida en un camión y se descargaban lanzándose en el agujero de lugares como este de la ciudad valenciana.

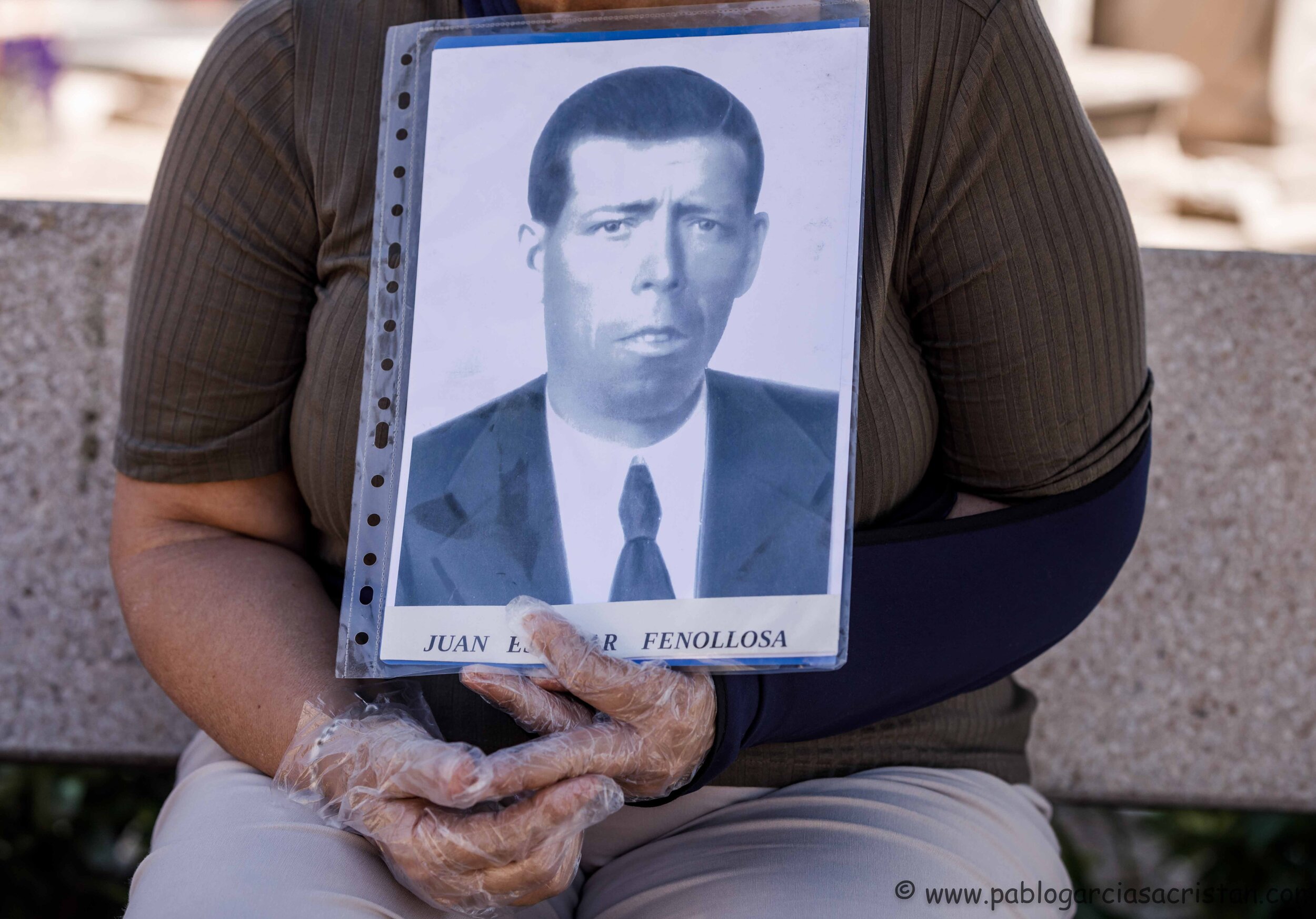

A partir de la fase 1 volvieron las visitas de los allegados, que coincidieron con la exhumación de los primeros cuerpos de esta fosa, donde todavía faltan meses de trabajo. Entre las primeras personas que acudieron el cementerio se encontraba Vicenta Juan, la nieta de Juan Escobar Fenollosa, padre de cuatro hijos que fue ejecutado el 6 de abril de 1940. Su abuelo, según nos cuenta, fue era un jornalero del campo y aficionado a la música cuyo “delito” fue acudir a un mitin de Manuel Azaña. Al terminar la guerra fue delatado por sus vecinos y fusilado. Además, a su mujer y a sus cuatro hijos los quitaron todas sus pertenencias y les obligaron a refugiarse en unas cuevas cerca de Manises.

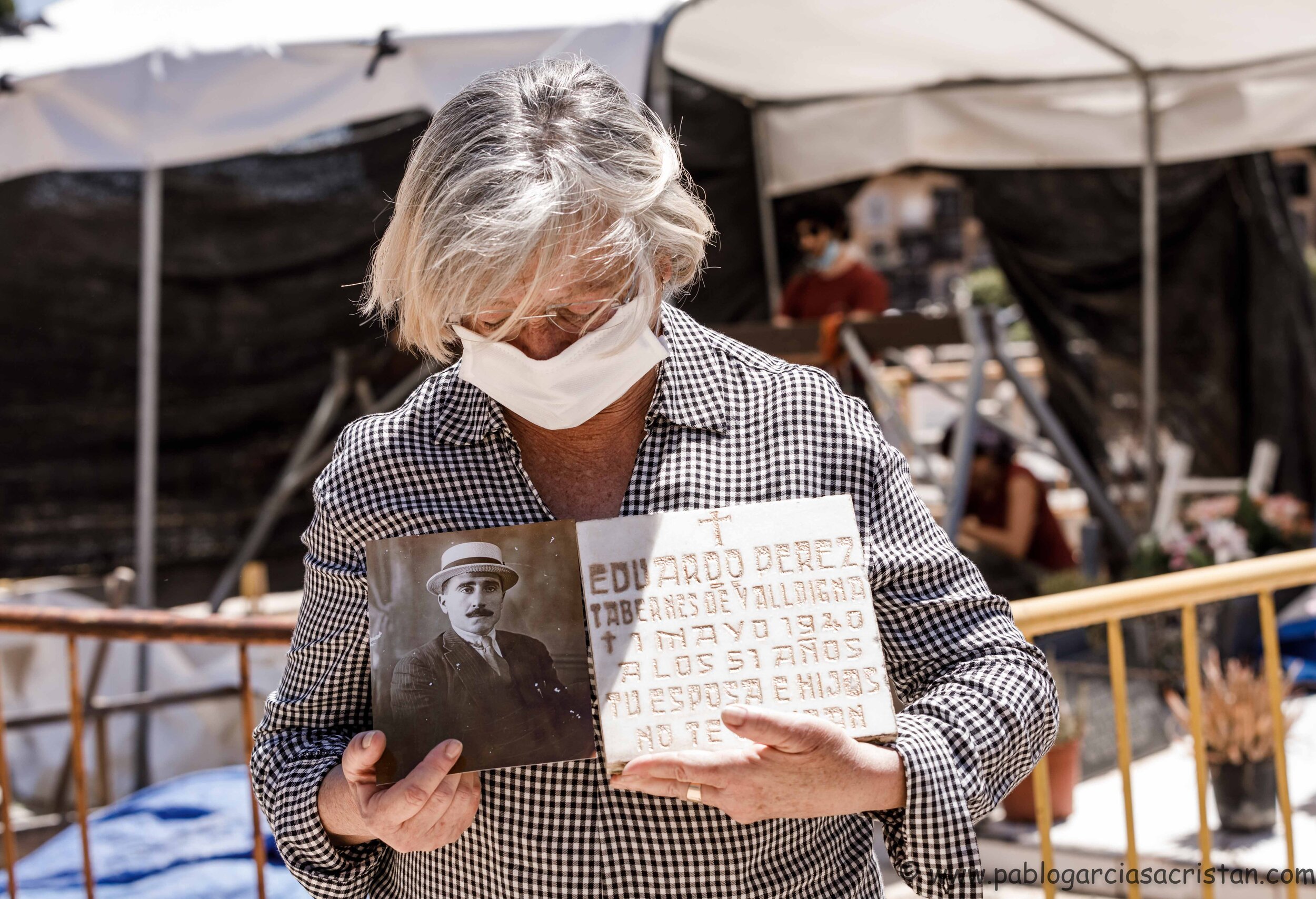

Otra de las personas que se acercó a Paterna fue Mercedes Pérez, nieta de Eduardo Pérez, teniente alcalde de la ciudad valenciana Tavernes de la Valldigna. Además, fue corresponsal del periódico Levante y miembro del sindicato de la CNT. Fue capturado intentando cruzar la frontera y fusilado a la edad de 51 años. Su nieta nos relata que sólo le quedan 2 fotos y el trozo de lápida en mármol que estaba al lado de la fosa común, que sirve para identificar los nombres de los muchos enterrados que existen en toda la geografía española. Mercedes necesita a su sobrino y a uno de sus hermanos para poder hacerse la prueba de ADN y que sea fiable, puesto que la genética no permite cotejar los datos de hombres y descendientes mujeres de carácter vertical.

“Mi abuelo está enterrado con sus dignos compatriotas que luchaban por unos ideales de igualdad y fraternidad durante la República y, por no pensar como los que mandaban, fue ejecutado vilmente en un paredón de fusilamiento”. Es la denuncia de esta mujer que, pese a ser población de riesgo de cara al Coronavirus, acude sin miedo buscando a su abuelo para poder enterrarlo dignamente y darle, por fin, un descanso merecido.

Antes del Covid19, los lugares donde se encuentran las fosas comunes estaban repletos de familiares que aportaban datos muy importantes para la exhumación de los cuerpos y para obtener informaciones de primera mano, pero la pandemia ha hecho que se retrase todo, dado a las estrictas medidas de seguridad y sanidad. Pero este camino nunca ha sido tarea fácil y sólo supone una piedra más que sortear para reconstruir el pasado y saldar una deuda histórica. Ha habido impedimentos legales y trabas de partidos políticos que han hecho más daño que el Coronavirus, pero la razón y la humanidad del colectivo de víctimas mantiene la esperanza de poder recuperar a sus familiares y cerrar esta lucha a la que han dedicado su vida.

Recover the past amid fear of the future

The pandemic has changed some of our preconceived customs and, also, our way of living and working, but it has not been a major impediment to continue recovering historical memory. Although during the hardest part of the confinement all non-essential activity was stopped, the works in the different graves located in the state have returned to adapt to the new measures. In addition to the complications caused by the security protocol and the difficulty of working more than two people together as it is a small space, the greatest damage caused by this crisis in the exhumation work is the lack of visits from family members. Although it may seem irrelevant, it is essential to compare the DNA of the buried remains in order to identify the victims. Fortunately, the relaxation of measures is allowing the people who want their loved ones to finally rest in peace.

This is the case of the Paterna cemetery in Valencia, which is known as "the mass grave of Spain", since its walls include more than sixty mass graves and around 2,300 people shot. Although everything stopped on March 15, from the beginning of April it was possible to return to work. Currently, the work is focused on grave 111, with more than 150 people buried who were shot (according to the data that is preserved from the registry and the memories of relatives) between the end of March and the first of May 1940. In each bag it ended with the lives of about 50 people, who were transported lifeless in a truck and were unloaded by throwing themselves into the hole in places like this in the Valencian city.

From phase 1 the visits of those close to them returned, which coincided with the exhumation of the first bodies of this grave, where there are still months of work. Among the first people who came to the cemetery was Vicenta Juan, the granddaughter of Juan Escobar Fenollosa, father of four children who was executed on April 6, 1940. His grandfather, according to what he tells us, was a day laborer in the countryside and fond of music whose "crime" was attending a Manuel Azaña rally. When the war ended, he was betrayed by his neighbors and shot. In addition, all his belongings were taken from his wife and four children, and they were forced to take refuge in caves near Manises.

Another person who approached Paterna was Mercedes Pérez, granddaughter of Eduardo Pérez, deputy mayor of the Valencian city of Tavernes de la Valldigna. In addition, he was a correspondent for the Levante newspaper and a member of the CNT union. He was caught trying to cross the border and shot at the age of 51. His granddaughter tells us that he only has 2 photos left and the piece of marble tombstone that was next to the mass grave, which serves to identify the names of the many buried that exist throughout the Spanish geography. Mercedes needs her nephew and one of her siblings to be able to get the DNA test and to be reliable, since genetics does not allow to compare the data of vertical men and women descendants.

"My grandfather is buried with his worthy compatriots who fought for ideals of equality and fraternity during the Republic and, not to think like those who were in command, he was executed vilely in a firing squad." It is the complaint of this woman who, despite being a population at risk for the Coronavirus, goes without fear looking for her grandfather to be able to bury him with dignity and finally give him a deserved rest.

Before Covid19, the places where the mass graves are found were full of relatives who provided very important data for the exhumation of the bodies and for obtaining first-hand information, but the pandemic has caused everything to be delayed, given the strict measures safety and health. But this path has never been an easy task and it only represents one more stone to overcome to reconstruct the past and pay off a historical debt. There have been legal impediments and obstacles from political parties that have done more damage than the Coronavirus, but the reason and humanity of the group of victims maintains the hope of being able to recover their families and close this fight to which they have dedicated their lives.

TEXTO

Toni Mejias @TonielSucio

FOTOS

Pablo García

Paterna, Valencia. Junio 2020